A pastor endures decades of hostility for defending biblical truth.

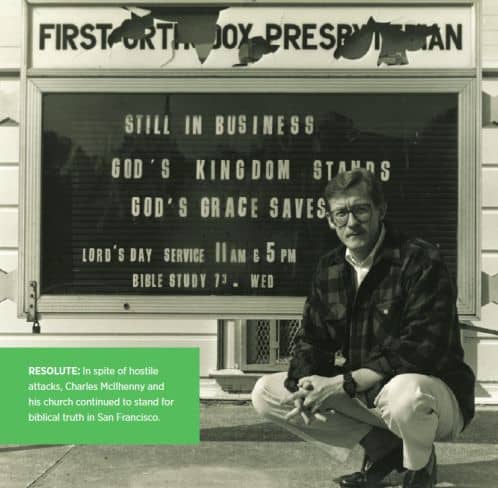

For some 35 years, Pastor Charles McIlhenny and his congregation, First Orthodox Presbyterian Church in San Francisco, withstood incredible hostility—even death threats and a firebombing—because he stood up for biblical truth in a city famous for celebrating homosexuality.

What McIlhenny faced may be a sign of things to come for many more churches and believers as Western culture abandons any semblance of biblical morality.

Subscribe to Decision

Get your own subscription, or renewal, or bless someone by giving Decision Magazine as a gift.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

McIlhenny’s ordeal began when his small congregation of about 50 members hired a new organist in 1978. During the interview process, the organist presented a credible sounding Christian testimony. But before long, McIlhenny discovered that the organist was a homosexual who saw no conflict between that lifestyle and the Christian faith. When the organist refused to recognize the Bible’s clear teaching on homosexuality, McIlhenny felt he had no choice but to fire him.

A few days later, McIlhenny answered the phone and heard: “You broke the law. Get a lawyer.”

McIlhenny learned that San Francisco had passed an ordinance that banned discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. There were no exceptions, even for churches.

For a few months, McIlhenny heard nothing more. But in the summer of 1979, he received a summons. The church, the presbytery and McIlhenny himself were being sued. He told Decision in a recent interview that initially he saw the suit as “a marvelous opportunity for the Gospel.” He never imagined the anguish the following years would bring or how the issue would define his career and ministry.

When local newspapers got wind of the story in early 1980, McIlhenny thought they would tell the story of a small church fighting against an oppressive city hall. Instead, the papers framed it as a church organist fighting for his rights.

“For the next three years,” McIlhenny said, “from January 1980 to 1983, it was perpetual death threats, phone calls, graffiti. The house and church, which were next door to each other, were constantly attacked.”

Eventually, the church won the lawsuit—which in some ways just made things worse. The media continued to tell the story from the point of view of the organist.

In spite of the attacks, McIlhenny never backed down or retreated to the shadows. News outlets called him for comments when they covered issues regarding morality, and McIlhenny boldly communicated biblical truth. In addition to the homosexuality issue, his church also housed a pro-life pregnancy center, putting the pastor at the epicenter of two explosive issues.

Shortly after midnight on June 1, 1983, McIlhenny, his wife, Donna, and their three young children were jolted awake as their house and church were set ablaze by arson, causing significant damage to both buildings. Two charred gas cans were found between the house and the church, but no perpetrator was ever caught.

McIlhenny wasn’t about to run away, and he wasn’t alone. A group of about 10 evangelical pastors stood together during those years, and they learned to mobilize quickly when issues arose, speaking out before the school board, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and other departments in local government.

“I began to be far more socially and biblically aware,” McIlhenny said. “What is the role of the church in the midst of a society that is clearly, publicly, legally contrary to Scripture? And if you’re going to take a stand on a biblical basis, what are the implications of that, and what is the involvement of the minister, the church, the congregation?”

In fact, McIlhenny’s first doctorate (he is working on his second) dealt with that very issue.

But he warns that when Christians stand publicly against the prevailing culture, they’ll develop a reputation. “Even in my own denomination, I was known as the pastor with the gay problem,” McIlhenny said.

As the years went on, McIlhenny faced continued attacks. From time to time, someone would pound on the doors and windows of his home at night. The house and church were graffitied so often that the congregation couldn’t afford to clean it up. After the windows of their daughters’ bedroom were smashed, the McIlhennys built a room in the center of the house for the children’s safety. Sometimes they had to send the children to stay with relatives in another city.

Finally, the McIlhennys had had enough. In 2005, they moved to Los Angeles, and McIlhenny began a new career as a hospital chaplain.

But even there, his reputation followed him. Despite a thriving ministry among patients and staff at the LAC+USC Medical Center, he was asked to leave in 2013.

He often hears Christians express the fear that if they take too strong a stand for Christ, they will be forced out of their position, and the witness for Christ will be lost. McIlhenny—who is now head chaplain at two other hospitals in addition to teaching and certifying chaplains in both private and public hospitals—bristles at that notion.

“Christ’s witness will never be lost, even if you are fired,” he said. “I dare say that if someone put a gun to your head and said, ‘Denounce Christ,’ 90 percent of Christians would stand for Christ. But if they said, ‘You’re not going to get your promotion or advance in your career or get that degree because of your stand for Christ,’ so many capitulate for those nauseating, trivial trinkets that the world can issue. … Dear Lord, have mercy on their souls!”

Followers of Jesus must be willing to face mocking, marginalization and even physical harm for the sake of Christ and His kingdom.

“There’s no neutrality,” McIlhenny said. “The Bible doesn’t allow for that. Our witness for Christ has to be public and clear—no matter what the government says.” D 2015 BGEA

Give To Where Most Needed